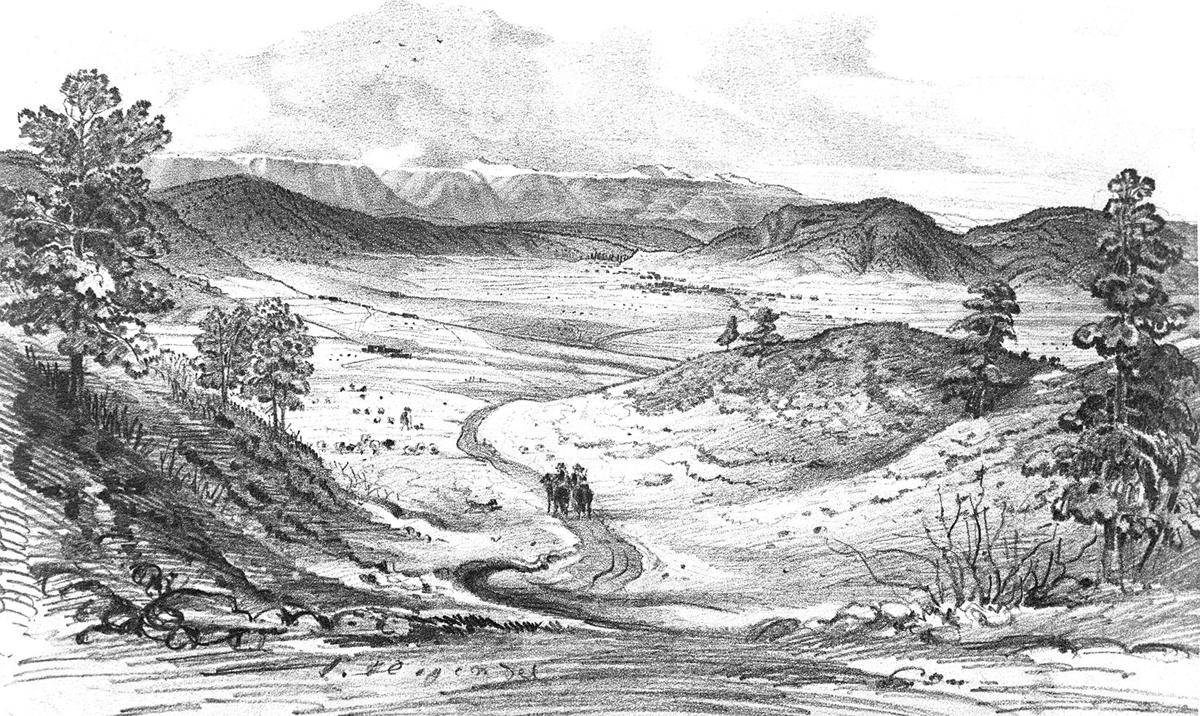

Ocate Creek Crossing

Imagine a land, a haven, with springs and creeks of crystal-clear cool water flowing downstream from neighboring mountains. These creeks are the center of all the communities, conflicts, and livelihoods all over this region. The tall New Mexico feathergrass and vital wooly Indian wheat in the basins of these ponderosa-filled mountain ranges, fed by the only source of water in the region for miles, dance in the breeze that has not stopped blowing for centuries now.1 The American Indian residents of this land named the region “port of the air” or “valley of the wind”, known in English as Ocate (Oh - Kah - Teh). The Ocate Creek Crossing and the small nearby town of Ocate lie at the end of the Cimarron Cutoff, a dangerous and arid branch of the Santa Fe Trail. Ocate, located in Mora County, New Mexico, was an oasis in all senses of the word and has been for generations of American Indians, Spanish colonizers, and Mexican and Anglo-American settlers.

Geography of the Mora County Region

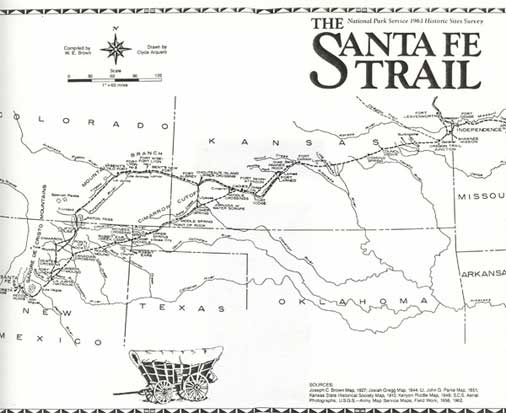

The land surrounding the Ocate Creek Crossing, popular with all manner of traders, raiders, and settlers, has seen many changes throughout the years. Ocate is an important location not only because of its geographic advantages, like having a source of fresh water and land for livestock to graze, but also due to the diversity of its inhabitants. This diversity can be directly attributed to the fact that the Ocate Creek Crossing lay at a very important juncture along the Santa Fe Trail. Ocate was a point of social, economic, and cultural interchange for many traders and travelers along the Trail. From there you could go north west into Taos through Manueles Canyon or further down south to Santa Fe by trails going through the Turkey Mountains.

This portion of the Trail was the first sight of any reliable source of water for almost two hundred miles. The creeks in the region refreshed travelers at the end of one of the most dangerous points on the Santa Fe Trail: the Cimarron Cutoff. The Cimarron Cutoff, also known as the Cimarron Route, was a preferred route because it avoided the steep terrain of Raton Pass and saved roughly 100 miles, but it also came with its hardships. The Cimarron Cutoff was very dry and known to be a hot-spot for Native resistance of colonization. Ocate Creek Crossing, however, is one of many creeks in the region that is known for being an area of comparative relaxation for those traveling on the Santa Fe Trail.

Mora County’s name is what some claim to actually be a product of people passing through it and the perception they had of that area. Although “mora” directly translates to mulberry in English from Spanish, there are no wild berries that grow naturally in the area. Many say that the name Mora may come from a Spanish family name, and that very well may be true as there are noted Spanish colonizers bearing that last name. However, one definition of the name Mora proves to be closely linked to the incredible resources this region provided compared to the preceding regions on the Santa Fe Trail. According to some of the earliest documents of settlers in the area, the name “Mora” was usually used in this manner. The area was often referred to as “demora” from the Spanish word “delay.” Many nicknamed the place “Lo de Mora” meaning a “stopping place”2. The region’s name is proof alone of this region being one of the most essential stops for many travelers, traders, and settlers following the Santa Fe Trail from modern-day Oklahoma into New Mexico.

Though the Ocate Creek Crossing itself is believed to be on a piece of private property in Mora County, many communities including Ocate, Los Manuales, and Los Naranjos owe their existence to this vital stream and other neighboring creeks along this portion of the Santa Fe Trail. Based on a population census done by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2010 and updated in 2018, Ocate has a population of just over 300 residents and Mora County in total has just above 4500 residents. However, most of the significance behind this region lies in its past and the role it had in shaping what would become the American Southwest from the 1500s to the early 20th century.3

American Indians and their Impact on the Area

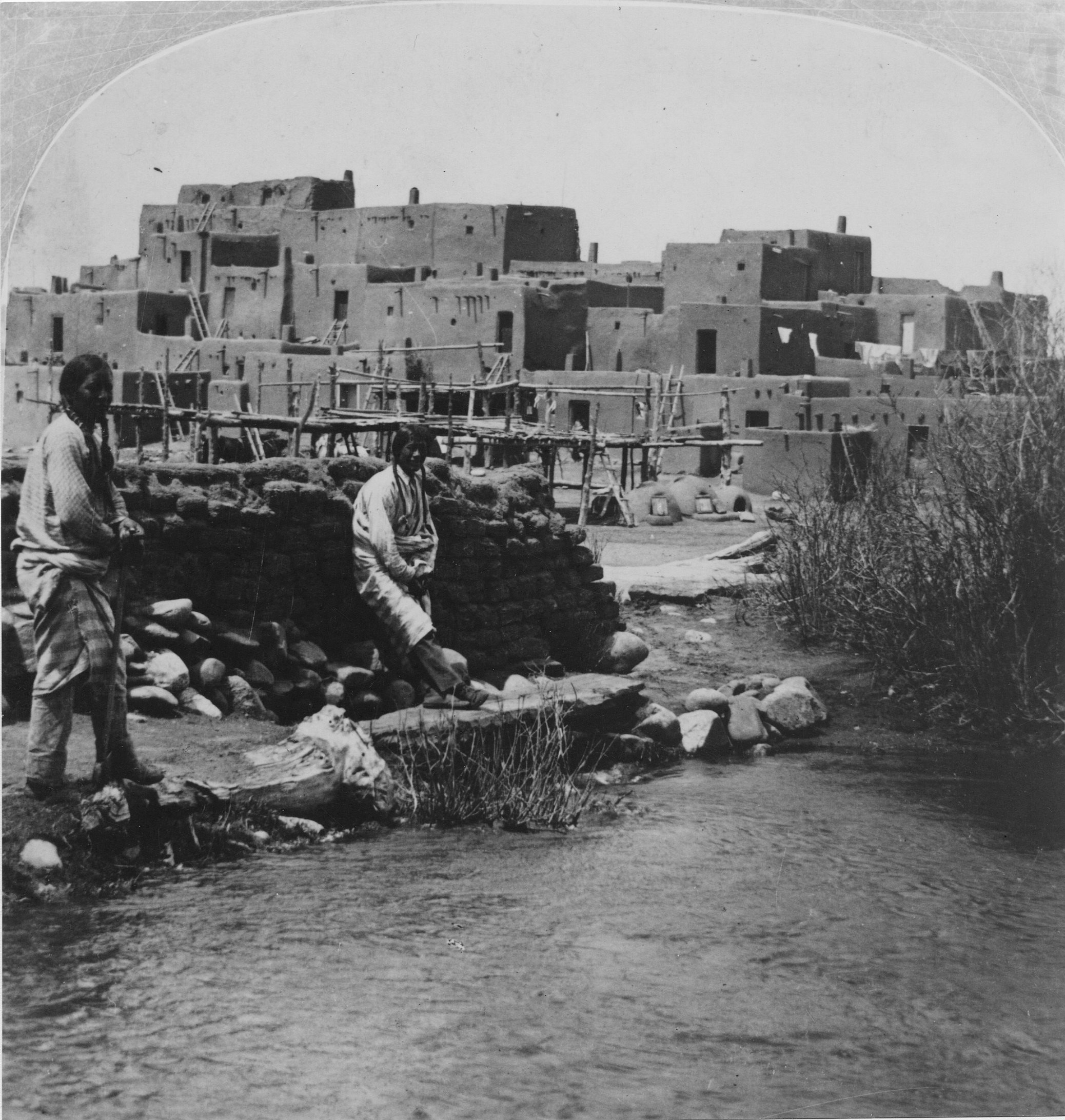

American Indians inhabited the present-day American Southwest thousands of years before anyone from Western Europe arrived. The region in which Ocate is located saw mostly Tewa, Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Jicarilla, and Ute tribes make use of this resourceful land. In particular, the Ocate Creek Crossing and the mountain ranges surrounding it served as a literal boundary between the Jicarillas and Utes, as a meeting point for trade amongst tribes, and later as a location to store stolen livestock from raids on Spanish settlements nearby. Many of the tribes in this area were small nomadic groups, so large-scale livestock grazing was not seen until the arrival of the Spanish with their sheep. Natives to this region relied on subsistence farming of wheat, wild oats, pumpkin, squash, peaches, cherries, and pears. Although the land did not legally belong to any one group of people, the Ocate region was an important home for many of the tribes’ natural resources such as fresh water and buffalo. Most of the sparse residential structures of the Indians who did live in the area were usually built with adobe.4 The convergence of American Indians in this area of northeastern New Mexico meant that several types of interactions occurred in the land. That led to many of the Native American nations embedding the land we now call Ocate with their own histories and cultures. Many traits and traditions from different tribes fused with others. The land itself became a neutral ground of sorts.

Spanish Colonization

The arrival of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado in 1540 marked the beginning of Spanish colonization in the region, and Ocate took on an entirely different meaning to the Indians there, who fought for almost 150 years to keep the Spanish at bay. Eventually, with the repression of a couple American Indian uprisings in the 1680s-90s and the signing of the Comanche Peace Agreement of 1786, things settled down at Ocate. After the peace agreements, Spanish settlers began establishing mutually beneficial trade systems with their Indian neighbors. Trading became part of everyday life in the region, and with it came the introduction of sheep; before this, wild buffalo were the only mammals in the region that provided both food and clothing. New trade networks emerged, facilitated by comancheros–Hispanic New Mexicans who made their living trading with Indian nations on the Great Plains, such as the Comanches.5 According to the granddaughter of an Indian woman who lived in the area in the mid-1700s to early 1800s, Comancheros traded “knives, serape blankets, and firearms for buffalo hides, meat and wild ponies.” Slaves and women were also traded, and more notably American Indian women and children were kidnapped and sold to traders along the Santa Fe Trail. Comancheros became important figures regarding relations between Indians and Spanish settlers during this time of open trade. Although there were some tensions that arose from this arrangement, it would prove to be a key element in maintaining the peace in the region around Ocate.6

Anglo-American Settlers

Native sources claim that many of the American Indian people were friendly and helpful to the settlers that came into the Ocate region. They proved to be indispensable to the settlement of this region by Hispanic, Mexican, and Spanish settlers. However, records also show that this friendly treatment may have only been extended to settlers of a certain heritage. Anglo-American settlers decided not to pursue the trading relationships that had been established between Native Americans and the Spanish. This caused tensions to rise between general groups of settlers and Native American tribes, especially the Apache, Comanche, and Kiowa. More and more raids began to occur as a result, and in many instances the Comanche and Kiowa tribes in particular would raid settlers and often let “Mexicans” escape freely while killing the rest.7 This distinction between Anglo and Hispanic settlers played a huge role in the relationships amongst the people who inhabited Ocate for generations to come.

Spanish, Mexican, and Hispanics & Their Relationship to the Land

The Spanish came exploring the southwestern region of present-day United States in the hopes of finding precious minerals such as gold and silver. Instead, they found a harsh and rugged foreign landscape equipped with native tribes to protect it from the unknown. The Spanish had a difficult time colonizing the region of Ocate. However, Ocate’s natural resources such as grazing pastures, access to fresh water, and proximity to timber from the nearby mountains made it a point of interest for many Spanish conquistadors. Their only real competition were the neighboring Indian tribes.

After almost a century of resistance from colonization, the Spanish began settling in the region with new-found peace. The Mora Valley area is proof of the permanence the Spanish associated with the land. Catholic churches and schools became the center of almost every community in the surrounding area. In the Mora Valley area, this religious iconography became a part of the cultural essence of the region. In particular, the image of “death” was iconicized through Godmother Sebastiana. The concept of death was relevant for both Hispanic and Native populations, and rarely seen as a taboo. Sebastiana was usually seen with a

“black shawl that covered her head, and her bony arms and her legs seemed always ready to poke out of the folds of her dress. Her image was unchanging, like that of the old villagers who dressed in mourning for years after the death of their husbands or of a son or a daughter.”

This saintly image of death served as a reminder to the Natives and Hispanics that eventually everyone would meet the same fate. It was noted that when the Americans began settling in the area, there was some noticeable tension regarding the Godmother Sebastiana; these new settlers had different views on death, and they interpreted veneration of Sebastiana as a way to pay tribute to “appease” the saint (motivated mostly by fear)8.

The Spanish and the neighboring Indian tribes interwove their lives, mostly through trade and intermarriage. Although conflicts did arise, trade routes proved to be an important form of cultural sharing, peace-keeping, and economic growth for both the Hispanic settlers and the American Indians.9 These trade routes also established the early permanent settlements in the Ocate area. Once the Americans arrived in the area, these trade routes and cultural ties were tested and often rejected, which created a new meaning of the land for the Spanish who had already been there for several generations. Anglo-American settlers viewed Hispanic and Native traditions in the region as entities that clashed with their own views. As both groups began to distance themselves from one another because of the American settlers domination of the landscape, the stress between the Spanish and Anglo-Americans ended up creating a new divide between the Spanish and Native Americans that had not been seen in almost a hundred years.

Ocate went from being a land that was seen as unattainable and full of conflict, to a land of generally unseen peace between Native tribes and foreigners, to a region permeated with division from the introduction of Anglo-American settlers. The Spanish helped shape Ocate into a region with a dynamic history full of turmoil, stability, cultural fusions, and by giving a sense of permanence to the land. The introduction of the Spanish to this region lead Ocate to being the modern town that it became in a span of less than 200 years.

Anglo-American Settlers Carving their Place in the Mora County Region

The Santa Fe Trail marked the source of most of the movement that came through Ocate by American settlers. Anglo-Americans, along with many Eastern European and East Asian immigrants, made their way westward in the name of Manifest Destiny and/or for gold said to be found out west during the Gold Rush in the early 19th century.10 After the Mexican-American War in 1848, Spanish and Mexican families who had already been there for generations were granted permission by the US government to keep their land. The Mora Land Grant Survey of 1835, conducted by the Mexican government in 1835 and confirmed by the US government decades later, confirmed to the US government that the lands in the possession of those Spanish and Mexican families for generations were in fact their own. Despite the majority of the land in the Ocate area belonging to Hispanic families at the time, most of the land gained by American settlers was acquired through questionable legal means or through the violent requisition of land owned by Hispanics or Native Americans. It is reported that 76 Anglo-American families settled in the region through these means. Because the Anglo settlers chose to stop participating in historic trade relationships established by the Native American tribes and Hispanic settlers, tensions arose.11

Violence against Anglo-American settlers occurred so frequently that a fort was built a few miles southeast of the Ocate Creek Crossing in order to protect the traders, travelers, and settlers (including American Indians, Hispanics, and Anglos) from the raids of Native Americans in the region. Fort Union, also nicknamed Fort “Windy” by the residents of the fort, was built in 1851 and sat in the grassy area between the plains and the mountains. Its prime location near fresh water, livestock grazing, and timber from the mountains made it an excellent post for the American settlers for almost 40 years after its construction. Its main function was to ensure the safety of the people living and passing through that portion of the Santa Fe Trail. However, Fort Union later became one of the most important Confederate forts in the southwest during the American Civil War. Military presence introduced a more stable environment for the American settlers. Ocate and its surroundings had become rather difficult to settle due to the constant raids, especially from the Comanches and Kiowas. After the fort was built, American culture was able to proliferate more freely and with less contention in the region. The Anglo-American experience and influence that they were able to gain in the region is tied to the military presence near Ocate. Although Fort Union’s impact should not be exaggerated, it would be remiss to assume that the fort’s presence had no repercussions on the land and the people surrounding it.12

With the settlement of more Americans in Ocate and the rest of northeastern New Mexico in general, the vegetation and the livestock in the land changed too. Anglo-American settlers preferred to raise cattle instead of sheep. This, along with other economic factors of the time, created a stark drop in the value of sheep in the region. This in turn lead to the economic decline of many Native and Hispanic ranchers in the region. Because of this change, many were driven to poverty and Native American raids of American and Hispanic settlers once again became common. As a result, many young men left the region to find more fruitful work in Colorado, Utah, and Kansas. This emigration from Ocate proved to be detrimental to the region’s popularity and is one of the major reasons why most of Ocate’s Hispanic and Native populations (and some Anglo populations) were never able to recover from the consequences brought on by American settlement in the area.13

Ocate’s Importance Then and Now

As a consequence of Westward American expansion, the Santa Fe Trail was eventually closed and lived on through the national railway system that was built in the late 1800s. Despite the railroad bringing more tourism to the west, Ocate, and the surrounding areas, experienced a sharp decline in population. Many of the raids of livestock that continued to happen and the general direction of the American economy were some of the main factors that led to Ocate essentially becoming a ghost town.

After the Santa Fe Trail was officially closed with the opening of the railroad, much of the Native and Hispanic presence changed in the region. Despite Ocate being at an important stop on the railroad for agricultural trade and being known as the most successful region for farming in New Mexico, much of those populations lived in poverty and experienced raids from outside tribes at a higher rate since the Americans first arrived in the area. However, despite Anglo farmers abandoning the area more often, Anglo-American presence in the region was still very prominent. In 1902, a collection of miscellaneous reports from the Governor’s office about all of the New Mexico counties from the Mine Inspector of New Mexico stated that Mora County was “one of the prettiest valleys of the US” and that this and the pristine air quality were some of the most attractive characteristics of the region. With the advent of the railroad system in the area, Mora County became a tourist attraction to Anglo-Americans in the early 20th century.14 Tourism and the agricultural sector in this region became vital solely because of its accessibility through the newly constructed inter-state railroad.

The region that was once characterized by the hustle and bustle of the Native trade routes and the Santa Fe Trail once again became relatively quiet. The American Indians that once roamed the forever windy region of Ocate have been driven out by the lack of natural resources available to them, the constant changing of the physical environment with new settlers, and by physical removal from the southwest into reservations through US policies and military involvement. As of 1994, the Ocate Creek Crossing sits on the National Register of Historic Places15 The Ocate region has seen some major transformations in the last 450 years. The land continues to mold itself through the people, animals, and natural life that are present (or not) in the region. Ocate will surely have a rich, interconnected, and multicultural history for the next 450 years to come.

Bibliography

Archaeological Tests and Ethnohistoric Research At La 74220, an Early Twentieth-Century Sheep Camp Near Ocate. Goodman, Schlager. Mora County, New Mexico. 1993. Accessed November 03, 2019. http://www.nmarchaeology.org/assets/files/archnotes/95.pdf#page=2&zoom=auto,-127,653http://www.nmarchaeology.org/assets/files/archnotes/95.pdf#page=2&zoom=auto,-127,653

Miscellaneous Reports, Part III. Pages 38 - 41.United States Department of the Interior. Governor of New Mexico. Mine Inspector for New Mexico. Mora County, New Mexico. 1902. Accessed November 25, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?id=gOo3AQAAIAAJ&pg=PA542&dq=mora+valley+county&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=Xved=2ahUKEwjCkOKhpoTmAhWK9Z4KHSA1ApMQ6AEwBHoECAIQAg#v=onepage&q=mora%20valley%20county&f=false

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. Ocate Creek Crossing and the Santa Fe Trail (Mora County Trail Segment) United States Department of the Interior, National Parks Service. March 11, 1993. Accessed November 07, 2019. https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/94000329

New Mexico Range Plants - Grasses. Allison, Ashcroft. College of Agricultural, Consumer, and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University. November 2011. Accessed November 07, 2019. https://aces.nmsu.edu/pubs/_circulars/CR374/

Santa Fe Trail Research Site, Fort Union, Chapter 1. Carolyn, Larry. St. Johns, Kansas. 2018. Accessed November 05, 2019. http://www.santafetrailresearch.com/fort-union-nm/fu-oliva-1.html

The Book of Archives. Melendez, Gabriel. Mora Valley, New Mexico. 2017. Accessed November 25, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?id=VwWNDgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=mora+valley,+new+mexico&hl=en&newbks=1newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiTxr7bkoTmAhUYpJ4KHRDeAGAQ6AEwAHoECAQQAg#v=onepage&q=mora%20valley%2C%20new%20mexico&f=true

The Place Names of New Mexico. Page 234. Julyan, Robert. Mora County, New Mexico. 1998. Accessed November 25, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?id=p3fMJnT1gx0C&pg=PA234&dq=mora+valley+county&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=Xved=2ahUKEwjn5dbEpYTmAhWBnp4KHUsMB-sQ6AEwAHoECAEQAg#v=onepage&q=mora%20valley%20county&f=false

3921 words.