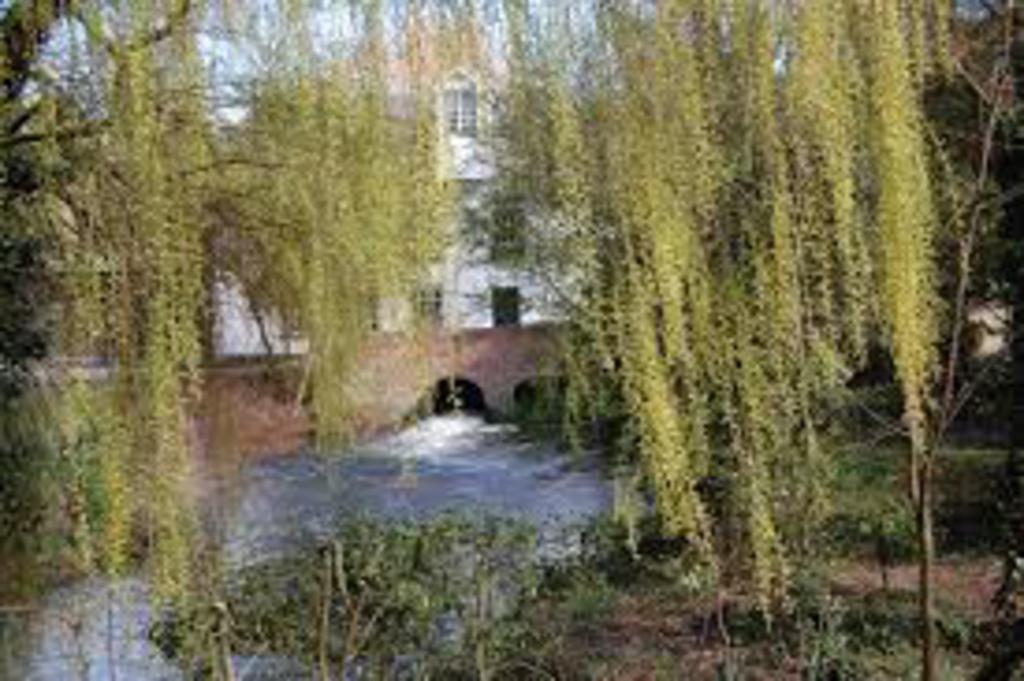

Blue Mills

Positioned approximately halfway between Fort Osage and the town of Independence, Blue Mills was an important center for provisioning traders and settlers on the Santa Fe Trail from the mid-1830s to the mid-1860s.

The Beginnings of Blue Mills

Long before the structures that provided its name, Blue Mills was known as an important crossing of the Little Blue River, mentioned in Josiah Gregg’s Commerce of the Prairies as part of William Becknell’s original route to Santa Fe.1 Yet by the 1830s, business interests controlled by Santa Fe Trail merchants Michael Rice, Samuel C. Owens, and brothers James and Robert Aull made new marks on the landscape. James and Robert came west in the 1820s, and by 1831 the brothers were partners with stores in four locations: Lexington, Independence, Richmond, and Liberty. Samuel Owens, who ran the store at Independence, also owned a tract of land up the Missouri River from Fort Osage that possessed a great landing. The growing popularity of steamship transport increased the value of this land exponentially; the Aull brothers capitalized on this trend, as well, by buying three steamboats. They also built a rope walk, a facility for transforming hemp into rope.2

Building the Mills

Father up the Missouri from Owens landing was Fort Leavenworth, the military complex charged with supplying troops throughout the American West. Local businessmen competed to supply the fort with staples, for these contracts were generally lucrative. The Aull brothers and their associates bid on one in 1834, but were outbid; as a result, James decided to construct a mill complex at the Little Blue River. The name ‘Blue Mills’ actually refers to two mills–a gristmill (constructed in 1834) and a sawmill (constructed in 1835). True to his goal, James won the 1835 contract worth $6,500 (roughly $168,000 today). These mills provided the businessmen with major advantages over their competition. The gristmill allowed them to make their own flour for resale in their stores, rather than purchasing it from eastern merchants; the sawmill produced lumber for stores and warehouses (and for sale, as well). The mills–situated on either side of an important ford along the Santa Fe Trail–could not have been more centrally located. By 1836, Owens Landing (named for its owner, Samuel Owens) had become known as Blue Mills.3

The Importance of Mills

Mills were generally rare on the western frontier of the United States, lending their owners a powerful position from which to negotiate. The scarcity of mills also meant that most people had to travel a long distance in order to get their corn or wheat ground; this was not a popular task, and one writer observed that “the settlers would gladly give one bushel of corn to get another one carried to mill and ground.”4 Not only was going to the mill unpopular, it was also dangerous. As one settler remembers:

I well remember my first trip to mill in Missouri. It was the last of December, 1853, when I and James Noel went to a water mill on Little Blue, built and owned by Benjamin Majors. I had sold a rifle gun to Wm. Rider, near the mill, for corn and other articles necessary for new beginners in the country. We shelled our corn at Riders, and took it to mill, and that night a deep snow fell, and before our load of meal could be ground, it had turned bitter cold; but with the assistance of the miller, Aleck Majors (afterward the great ox driver across the plains), we loaded up and got over the icy and dangerous crossing of the Blue, and set out for home. We had a five horse team, and twenty odd miles before us. Noel rode the saddle horse and drove the team, until to avoid freezing he would jump off and run by its side, till tired and exhausted, he would mount and ride and whip again. In the same manner, I rode in the wagon, and ran in the snow behind it by turns. Dark came on, and oh! how cold - how bitter cold. To make matters worse, in crossing a ravine at the head of the creek, our team became tangled in the gearing, and some of it was broken or came loose, in arranging which Noel’ s fingers were frozen, and I fell into the ravine, and so twisted one knee as for a time not to be able to walk. He, however, managed to get hitched up again, and I man aged to get in the wagon, and he drove Jehu-like until we reached the house of Isaac Dunnaway, who opened his hospitable door, and saved us from freezing to death.5

From a harrowing story like that, it becomes obvious why owning a gristmill (and a lumber mill) would prove extremely beneficial in the nineteenth century.

The Mills Expand

In 1835, Robert Aull left Liberty and took charge of the flour mill at Blue Mills; soon afterward, his brother applied for a post office to be established around the mill (with Robert as its postmaster). A small but bustling town soon grew up around the mill, even featuring its own newspaper. Seventeen men worked at the gristmill and lived at a nearby boarding house. The sawmill sold planks and shingles made of walnut, oak, and sugar maple.

Despite the growth of this little town, Blue Mills impacted markets far and wide. Flour from the gristmill went to Independence, St. Joseph, and Fort Leavenworth; it also went farther afield to places like St. Louis, New Orleans, and even Europe. As steamboats grew more common, the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail moved westward to the town of Independence by the early 1830s. Blue Mills thus became an important point for the change-over between water and land transport; in fact, an immense warehouse was built to protect goods awaiting overland shipmentJackson2. According to one source, “countless tons of trade goods bound for Santa Fe went up to Independence from this landing”; Blue Mills also became an important water-to-land transfer point for migrants heading westward.6

Blue Mills’ Decline

By the 1850s, communities like Westport and Kansas City became more popular; however, the mills at Blue Mills operated consistently into the early 1860s.7 They were in ruins by the 1920s, and one man found workers clearing away debris and preparing to roll the millstone into the Little Blue. Yet the site remains important for many reasons: as a reminder of the importance of milling to the frontier experience; as an example of the (inter)national connections fostered by the Santa Fe Trail; and as a casualty of the ever-present competition between different landing points along the Missouri River.

Bibliography

Enscore, Susan. “Blue Mills.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. Urbana, Ill.: The Urbana Group, 1993.

Hickman, W.Z. History of Jackson County, Missouri. Topeka, Kans.: Historical Publishing Co., 1920.

Union Historical Company, The History of Jackson county, Missouri, containing a history of the county, its cities, towns, etc., biographical sketches of its citizens, Jackson county in the late war… history of Missouri, map of Jackson county …. Kansas City, Mo.: Birdsall, Williams, and Co., 1881.

1231 words.